Planning Instruction

Thoughtful planning is a central part of an effective Intentional Read Aloud.

The Many Uses of Intentional Read Aloud in the Classroom

Listen to a teacher reflect on some of the ways that she finds IRA to be beneficial in her classroom.

Of course, not every read aloud needs to be intentional. There’s nothing wrong and a lot right with picking a favorite book off the shelf, gathering the children on the carpet and reading aloud for the sheer pleasure of it.

But reading aloud can also be a powerful instructional tool. And the only way to get the full potential out of your lesson is by careful and thoughtful planning. This planning is what makes the read aloud intentional.

When you plan, you consider:

- The learning goals for your children

- The language outcomes for your children

- How your lesson can support other literacy practices or instruction in the content areas

- Which book will support your goals

After you choose your book, take time to read through it thoroughly. Think about the background knowledge of your children, confusing parts of the text, new formats or features that you’ll need to go over and vocabulary words that you’ll want to introduce. Think about how you will engage your children as they are listening. Plan ways for them to talk about the text, try out new skills, and maybe even join in the reading. Use the Intentional Read Aloud planning template to write down your ideas. A thoughtfully planned read aloud will be more focused, valuable, and enjoyable for your children.

Lesson Planning Templates

The lesson planning template is your partner in planning a successful Intentional Read Aloud lesson. The template is equipped with helpful prompts that focus your attention and support your thinking through the planning of each lesson component. If you need more support, take a look at our “notes” version of the template. Use the sample lesson plans for ideas and feel free to adapt them to use in your own classroom.

2nd Grade Sample IRA: An Egg is Quiet

Use this sample lesson as a guide to teaching text structures in informational texts.

1st Grade Sample IRA: Bernice Gets Carried Away

This sample lesson shows one way to teach about character in literature.

3rd Grade Sample IRA: Eleanor, Quiet No More

This sample lesson introduces the comprehension strategy of questioning.

Kindergarten Sample IRA: One Duck Stuck

This sample lesson explores hearing and generating rhymes.

2nd Grade Sample IRA: Surprising Sharks

This sample lesson teaches how to use captions to deepen our understanding of an informational text.

Intentional Read Aloud Planning Template

Use this lesson plan template to guide your own planning.

Intentional Read Aloud Planning Template (Spanish)

Use this lesson plan template to guide your own planning.

Intentional Read Aloud Planning Template: Notes Version

This 'notes' version of the planning template offers more support as you plan your lessons.

Choosing Objectives

The first thing you need to consider as you are planning is the learning goal for the children. Carefully select the primary literacy objective to keep your lesson focused, meaningful, and engaging. Make sure the objective meets the needs of your children. Here are some considerations for choosing objectives:

Choose objectives for your read aloud based on your curriculum’s scope and sequence, mandated learning standards, and the needs of your children.

Make sure the objective is appropriate for the majority of the children in the class (not just a few children).

Keep a list of read aloud objectives as you teach them, along with the corresponding books. This will help you keep track of the skills, strategies, and behaviors you have taught and help with future planning.

If you already have a book in mind, look at the format, genre and/or theme to help formulate your objective (while still keeping the above guidelines in mind). See the chart below for examples:

| Genre/Theme/Format | Possible Goal for Read Aloud |

|---|---|

| Informational Text | Text features, main idea |

| Poetry | Descriptive language, rhyming, vocabulary |

| Alphabet book | Phonics/phonemic awareness |

Spy on your own reading by noticing the behaviors that you engage in as you read (i.e. envisioning, decoding, monitoring for comprehension, etc.) Use this information to guide the selection of your objective.

When appropriate, select objectives that connect to other areas of literacy instruction such as writing, word study, etc. If the children are writing “how to” pieces in Writing Workshop, you could read a “how to” book and ask the children to notice what makes this type of writing unique. If they are learning about verbs in word study, they can identify the verbs that they hear during the read aloud and discuss how these words enhance their comprehension of the story.

Choose objectives that cover different areas of reading instruction – phonemic awareness, vocabulary, comprehension, or fluency.

Most high quality books lend themselves to many different objectives. Don’t get overwhelmed. Remember that you can and should return to books multiple times and reread for many different purposes.

After teaching a read aloud, reflect on the evidence of children’s learning and whether or not the objective needs revisiting.

Choosing Books for Intentional Read Alouds

Children are capable of listening to books that are well above their independent reading level. Intentional Read Aloud is a good time to expose children to rich vocabulary, interesting language, and complex ideas that they are unable to read yet on their own. Increase the complexity of the text as the year goes on and your children’s listening comprehension increases.

Connecting Your Book Choice to Your Lesson Objective

Strategies for connecting your book choice to your lesson objective.

Select books that are interesting to your children. Consider their background, experiences, and culture. Take interest inventories of favorite authors and books, use your own observations, or check reading logs to see what kinds of books are appealing to your children.

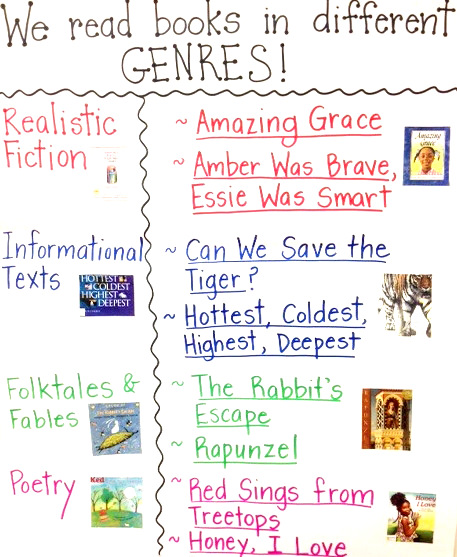

Choose books that broaden children’s experiences and expose them to new concepts and ideas. Introduce children to new topics, genres, and authors to widen their reading range.

Choose books that support your primary literacy objective, your curriculum scope and sequence, or mandated learning standards. For example, if your goal is to learn about characters, choose a book where the character’s feelings and actions are central to the plot or theme of the story.

Connect your book selection to themes and/or content areas. See the following examples of book titles and their related connection:

| Book Title | Connection | Grade |

|---|---|---|

| But Excuse Me, That is My Book | Library Procedures | K |

| My Granny Went to Market | Counting/math | 1 |

| On the Same Day in March | Weather/science | 2 |

| Eleanor, Quiet No More | Emotions/feelings | 3 |

Choose books that lend themselves to rich conversations. Books with themes, plots, and characters that children can connect to and find interesting will promote meaningful class discussions.

Choose high-quality books that are well written, have memorable characters, engaging plots, and rich illustrations, photographs, or graphics.

Choose texts that you love yourself. Your enthusiasm will transfer over to your children and increase their excitement during the read aloud. It will also encourage them to read books that they might not have selected before.

References:

Calkins, L. (2002) The art of teaching reading. New York: Addison Wesley Educational Publishers, Inc.

Collins, K. (2004) Growing readers. Portland: Stenhouse Publishers.

Fountas, I., & Pinnell, G. (2011) The continuum of literacy learning. Portsmouth: Heinemann.

Checklist for Pre-Reading

Pre-read books before reading them aloud to your children. Become familiar with the content, rehearse pronunciation, expression, and fluency, and mark areas for think alouds and class discussion. Children will be more engaged and class discussions will go deeper if you are thoughtful about how you will read the book. Here are some things to look for when pre-reading a text:

Pre-read books before reading them aloud to your children. Become familiar with the content, rehearse pronunciation, expression, and fluency, and mark areas for think alouds and class discussion. Children will be more engaged and class discussions will go deeper if you are thoughtful about how you will read the book. Here are some things to look for when pre-reading a text:

Think about the central message or theme of the book. If there was only one thing you wanted children to understand after reading, what would it be? What can you do to help children understand the central message?

Consider the background knowledge and cultural experiences of your children. Is there anything specific that you want to highlight for them before or during reading? Are there concepts they need to support their comprehension and make the overall experience more successful?

Pay careful attention to the illustrations and text features such as graphics, headings, and captions. Is there anything particularly unique or unfamiliar that you want to share with the children (or hope that they will find on their own)?

Note any language constructs and features that could be confusing or unknown. This might include dialogue, quotes, speech bubbles, figurative language, dialect, unfamiliar syntax, or foreign words and phrases. Think about how you can shelter English language learners to support comprehension.

Note any text structures that might be new or confusing such as: multiple characters, flashbacks, unique settings, shifting points of view, or a story within a story.

Make a list of possible Tier II or Tier III vocabulary words to highlight. Decide on a few words to highlight and write child friendly definitions for those words.

Notice words with unfamiliar pronunciation (i.e., different languages or dialects, scientific or other content-related words, unique names for the character, author, or illustrator) and learn how to pronounce them before reading (by asking a colleague, searching for the phonetic spelling, etc.).

Read the book out loud to practice fluency, intonation, and expression. This will help you to realize if there are areas where you need to slow down, change your voice level due to punctuation, etc.

Decide whether you will read all the print on the page and in what order. In Miss Malarkey Leaves No Reader Behind, for instance, there are book lists, speech bubbles, and other print on each page, in addition to the story text. Knowing what you will read (and in what order) will make the read aloud run more smoothly.

Use sticky notes or tabs to mark a few places in the text where you plan to think aloud, ask questions, talk about vocabulary, or add to an anchor chart.

Decide whether you will read the entire text in one sitting or separate it into multiple readings. This decision will depend on the length of the book, its content, the primary literacy objective, and the age of the children.

The Role of Anchor Charts in an Intentional Read Aloud

“We honor children and their thinking when we capture it precisely. Whether we’re creating an anchor chart or recording quotes for display…authenticity is essential. The reflections, quotes, ideas, and big understandings displayed throughout a room should reflect the real voices of real kids.” - Debbie Miller, Teaching With Intention, 2008

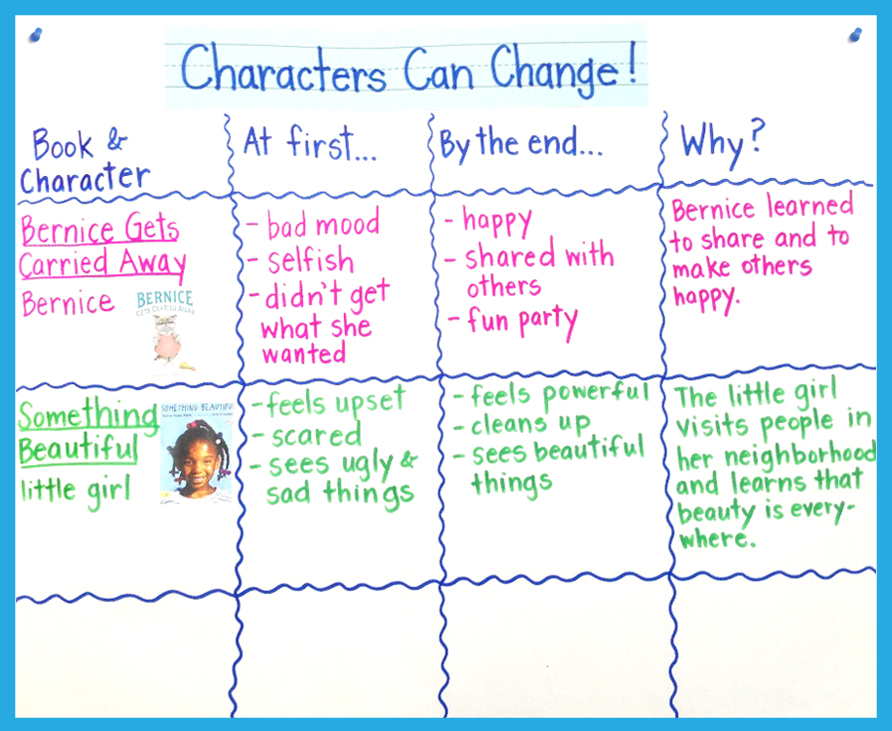

The anchor charts you create with children during an Intentional Read Aloud help you connect skills and strategies to other practices in your literacy block. Anchor charts bridge the learning from modeling to guided practice to independence.

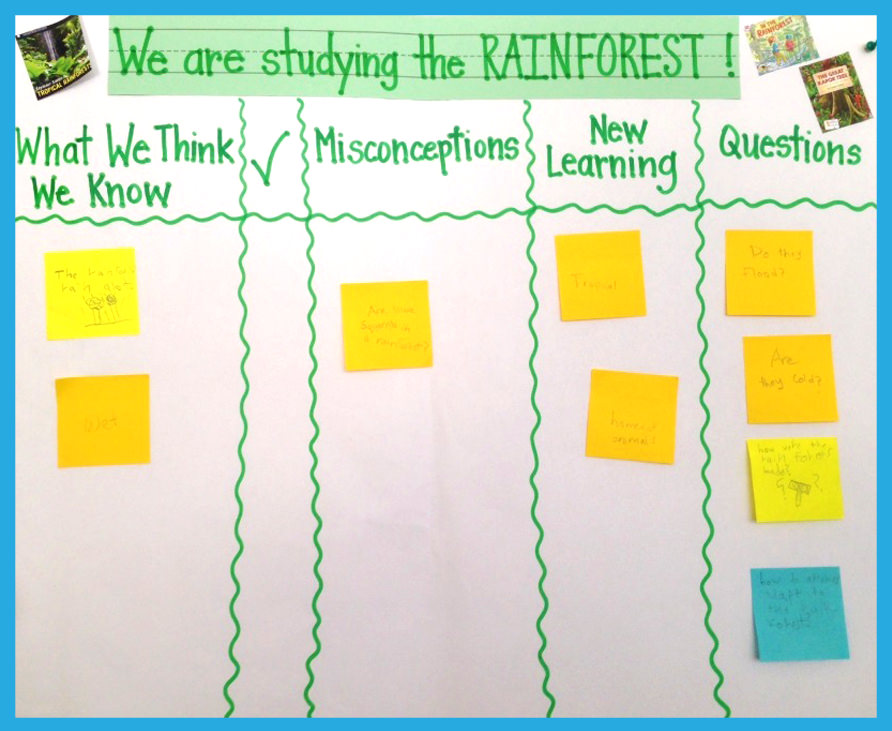

Anchor charts make the thinking and learning of the children in your class visible. They are reminders of the skills, strategies, ideas, and vocabulary that children are learning. Create anchor charts with children to explore a skill or strategy, capture children’s ideas, and connect to the literature you are sharing together.

Here are ways you can use anchor charts during an Intentional Read Aloud:

- Connect the skills, behaviors, and strategies children are using to the literature you are reading. This helps children think more concretely about the skills they are learning. It gives everyone in the class a real life example to reference and helps connect concepts from book to book.

“Class, do you remember when we read Bernice Gets Carried Away? We talked about how sometimes characters change in the story. Well, we are going to do the same thing today as we read Something Beautiful. Let’s see if the little girl in this book changes like Bernice did.”

Encourage children to take an active role in creating the anchor charts. Capture your children’s thinking by recording their ideas on the chart, or having them add to the chart directly or with sticky notes.

Use anchor charts to showcase for children, parents, and visitors the learning that is taking place in the classroom. Anchor charts should reflect the strategies being taught, the books that are being read, and the content areas and themes children are exploring.

• Build anchor charts over time. Add to charts as children’s thinking grows and changes. Use anchor charts to remind children of learning throughout the year. |

• Use the anchor charts to connect learning to other practices in the literacy block. For example, you can create an anchor chart during the read aloud and use the chart to remind children of a skill, strategy, or behavior in Reading Workshop, Writing Workshop or Guided Reading. “Remember when we made text-to-self connections when we read Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day together? We are going to practice that same strategy today in our Reading Workshop.” |

Repeated Readings of Intentional Read Alouds

As teachers, we might groan a bit about reading the same book multiple times, but there are good reasons why children like it. Hearing the same story again and again feels safe and secure. The words, pictures, and even your intonation and expression is predictable and comforting to children.

Rereading favorite books is not just enjoyable for children, but helpful, too. Children learn through repetition. A study on language acquisition found that children pick up new vocabulary more quickly from repeated readings of the same book than when they encounter the same words in different new texts (Horst, Parsons & Bryan, 2011). This is especially helpful for English language learners. Multiple readings of the same book support them as they learn new words, phrases and sentence structures.

When you reread books to children, the conversations around them get richer and richer. Children’s understanding deepens as they get to know the characters better and notice new things in the book. Their focus shifts from understanding what is happening in the story to big ideas around author’s message and theme. Researchers found that children’s responses to questions during rereading grow in variety and complexity. They are able to make more associations, judgements and elaborative comments. (Morrow, Frietag & Gambrell, 2009)

Sharing books that the whole class knows and loves builds a culture of literacy and sense of community in the classroom. It gives everyone a common language with which to dig into one story and a solid base for exploring new ones. (Horst, Jessica S., Kelly L. Parsons, and Natasha M. Bryan. “Get the story straight: Contextual repetition promotes word learning from storybooks.”Frontiers in Developmental Psychology 2.17 .2011.: 1.11.)

Morrow, Lesley Mandel, Elizabeth Freitag, and Linda B. Gambrell. Using Children’s Literature in Preschool to Develop Comprehension: Understanding and Enjoying Books. International Reading Assoc., 2009.

Comments (1)

Log in to post a comment.