During Reading

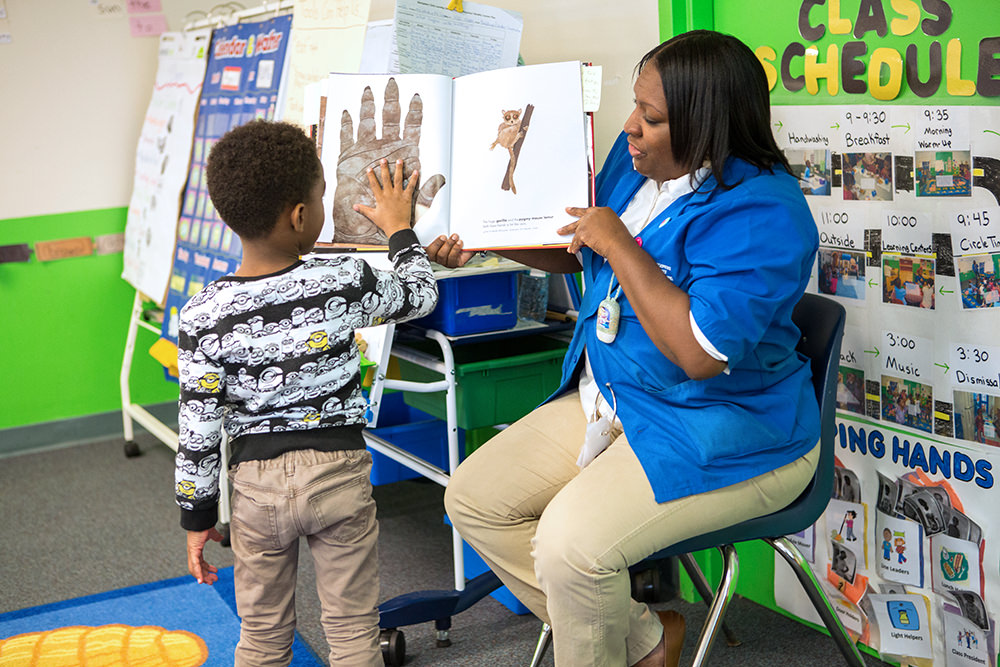

After you’ve introduced your book and set a purpose for listening, you are ready to get to the good stuff – reading, sharing, and discussing the text with the children.

This is the meaty part of your Intentional Read Aloud. It is your opportunity to model what good readers do and build children’s understanding.As you read aloud, model fluent reading to support children’s comprehension. Stop during selected parts to think aloud, ask questions, and reinforce your primary literacy objective. Have children participate in the lesson by giving them opportunities to think about, respond to, and join in the reading.

Teaching Comprehension through an Intentional Read Aloud

We read with children for many different reasons. We read to learn something new, to build a sense of community, to connect our own experiences to others, to explore ideas different from our own, and to understand how other people live, feel, and think. The list could go on and on. But at the heart of all these things is understanding – making sense of what we read.

Comprehension is at the center of what we do as readers, listeners, and thinkers. In fact, it is the sole purpose for reading. Every reading skill, strategy, and behavior we teach children, from accuracy and fluency to building vocabulary and background knowledge, is in service of comprehension.

Comprehension is at the center of what we do as readers, listeners, and thinkers. In fact, it is the sole purpose for reading. Every reading skill, strategy, and behavior we teach children, from accuracy and fluency to building vocabulary and background knowledge, is in service of comprehension.

Teaching comprehension through an Intentional Read Aloud is a natural fit. Intentional Read Alouds provide you with the time, opportunity, and community to discuss how effective readers make meaning from books. Here are some ways to build children’s comprehension during Intentional Read Aloud:

Think Aloud - As the most proficient reader in the classroom, your description of how you make meaning from a text is important. When you think aloud for children, you give them a window into the thought processes behind making meaning. Plan for one to three demonstrations of how to comprehend a text or a portion of a text to provide children with the information they need to make meaning independently.

Conversations - Actively encourage children to think about, talk about, and make meaning of the text. You can have whole class discussions or have children share with a partner. The more children can actively engage with a text and its ideas, the more they will comprehend.

Text-Based Evidence - Ask questions that require a response that includes information from the text to ensure that children are keeping their thinking grounded in the text and are participating in close reading.

Open-Ended Questions - Pose questions that encourage conversation and do not demand a correct answer. This gives children an opportunity to work on their analytic skills, extending their comprehension of a text more globally.

Close Reading - Direct children to a portion of a text and ask them to think deeply about its structure, the vocabulary, or the author’s purpose. This exercise not only helps children comprehend that particular text (or portion of the text), but can be a model for how to approach independent reading as well.

Anchor Charts - Use anchor charts to capture children’s thinking about comprehension skills. They can be used to guide conversations before, during, and after the Intentional Read Aloud and can serve as a visual aid and reminder for the important ideas you are teaching.

Reread Books or Portions of Books - The value of rereading cannot be overstated. The more familiar children are with a text, the more their comprehension develops. Revisit favorite texts to construct meaning and highlight different skills and strategies. This will offer children the opportunity to concentrate on their metacognition and allow them to think more deeply about a text.

Solicit Questions from the Children - Ask children what questions they have about a book. This will give you insight into what they are thinking and give children a chance to think about and evaluate their own understanding.

How to Model Your Thinking

When you read, your brain is engaged in a complicated process of figuring out, interpreting, and making meaning of the author’s words. This process of comprehending a text happens inside your own head, invisible to everyone but yourself. When you think aloud, you are making this invisible process visible to children. You are showing them how experienced readers make meaning from a text, so that they can learn to do it on their own. Some children figure out these processes on their own, but many do not. Thinking aloud is an essential support for both language learners and struggling readers.

Here are some ways to make your “think alouds” clear and effective:

Listen in on yourself as you pre-read a book for your Intentional Read Aloud. Were there places you had questions? Or thought, “Aha. I think I know what’s going to happen next.” Did you make any connections to the story? Use your own thinking to guide your planning for your think alouds.

Choose one skill or strategy to focus on for your think aloud. Select one to three stopping places in the book where you can demonstrate how to use the skill or strategy to your children. For example, if you are teaching inferring, choose a few places in the book where you made an inference that helped you understand the book.

Rehearse what you will say during your think aloud. Jot down your thoughts on a sticky note and place the note in the book at the stopping point.

Let children know when you are thinking aloud. Put the book face down on your lap and point to your head. Use explicit words like, “So far, I’m thinking…” These visual and oral cues make it clear to the children that you are thinking, not reading from the book.

Use child-friendly language. This is the language that you want children to use when they are reading and thinking on their own. Share tips for what careful readers do. For example, “We just read four pages. This is a good spot for me to stop and check to see if I know what is happening in the story. Careful readers always check to make sure they know what is happening.”

Here are some helpful phrases to use in your think alouds:

- Let me stop reading now and share my thoughts with you…

- I wonder why…

- So far, I’m thinking…

- Hmm…I didn’t really understand why… I better re-read this part…

- This is what I have noticed so far…

- When I read this… I think…

Modeling Fluency

“There’s no exact right way of reading aloud, other than to try to be as expressive as possible. As we read a story, we need to be aware of our body posture, our eyes and their expression, our eye contact with the child or children, our vocal variety and our general facial animation. But each of us will have our own special way of doing it.” - Mem Fox

Read fluently and expressively to make the story come alive for your children. They will be more engaged, understand the text better, and have a model for what their own reading should sound like.

When you read fluently and expressively, you demonstrate your own interpretation of the character, information, and concepts in a book. Your tone, phrasing, pacing, and mood all help children make sense of the story. Your expressive reading is a scaffold for children’s comprehension. This is one reason pre-reading books is so important. You want to make sure you are interpreting the book in a way that makes sense and doesn’t get in the way of children’s comprehension.

Read smoothly and with expression to your children, so they know how fluent reading should sound. Children will transfer these behaviors to their independent work, making it more likely that they will comprehend what they read. Reading with fluency also increases child engagement and overall enjoyment during the lesson.

Guidelines for fluent reading

Change your voice to match the character’s personality and feelings. Your voice can sound happy, sad, excited, or frightened to match the events in the text.

Change your pacing to build anticipation and a sense of drama and to reflect the action of a piece of writing.

Use non-verbal cues to support children. Your facial expressions and hand gestures can help to tell the story or make the text come alive.

Pay attention to rhythm, pitch, stress, and pacing to get the author’s words and meaning across.

Choose some read alouds to explicitly teach fluency to children. Ask children to be “detectives” and notice what fluent reading sounds like. Discuss their ideas and add them to a chart that they can use to monitor their own fluency.

Strategies for Engaging Children

So many children’s books invite participation. Children love to move like the animals in Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?, huff and puff along with the big bad wolf, sing with Skippy John Jones, or chime in on the rhymes during Bee-Bim Bop. Reading is not a passive activity, and we certainly don’t want children to be passive listeners as we read aloud to them.

So many children’s books invite participation. Children love to move like the animals in Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?, huff and puff along with the big bad wolf, sing with Skippy John Jones, or chime in on the rhymes during Bee-Bim Bop. Reading is not a passive activity, and we certainly don’t want children to be passive listeners as we read aloud to them.

There are so many ways to get children involved and connected to what we read. They can share their thoughts and feelings, discuss their ideas with friends, and react to the words and pictures in the book. Encourage children to participate in the read aloud to get them more excited about the book and more invested in the lesson.

Vary your engagement strategies so that ALL children can be actively involved in the read aloud. Keep in mind that English language learners may understand far more than they can produce. If a child does not speak out, it does not mean they don’t have something valuable to contribute. Be thoughtful about the types of interactions you are eliciting from children so that everyone can participate. Asking children to give a thumbs up or show a “me too” signal are some non-verbal ways to get everyone involved.

Here are some ways to encourage children to participate:

- Echo or choral read words or parts of the book (like rhyming words or repetitive phrases).

- Respond to questions and think alouds during the reading.

- Think, turn, and talk to discuss ideas with partners.

- Act out vocabulary words or the feelings of the characters.

- Use props to act out characters’ roles in the story or to focus on features of the book such as dialogue or speech bubbles.

- Lend their ideas to anchor charts during and after the story.

- Stop and jot or draw a response to the story on a dry erase board or in a notebook.

- Listen for something specific in the text and use a silent signal of recognition. Choose something for the children to listen for such as: figurative language, describing words, or rhyming words.

- Teach silent signals for text-to-text, text-to-self, and text-to-world connections.

- Use silent signals for “me too” and “I agree” when participating in conversations.

- Use oral cloze strategy to guess the word based on the rhyming sound, knowledge of the story, or other clues.

Asking Open-Ended Questions

Give children opportunities during the read aloud to respond to open-ended questions about the book. Children build their comprehension as they talk and think through ideas and listen to their peers. Open-ended questions don’t have right or wrong answers and can’t be answered with just a yes or no. These questions should encourage children to reflect, react, and connect to the story. Examples of open-ended questions include:

- “What do you think the character might be thinking?”

- “What do you wonder about after reading this section?”

- “What do you think might happen next?”

Answering open-ended questions and having conversations about books improve children’s listening and speaking skills, deepen their comprehension, encourage higher-level thinking, and develop their vocabulary.

Children’s answers to questions offer an opportunity for you to check their understanding. Did they understand the problem in a story? Can they explain what happened? Do they remember important details? Can they make useful predictions and connections?

Listen closely to children’s answers. Encourage children to link their thinking to evidence in the book. Ask follow-up questions such as, “What in the story made you think that?” or simply, “How did you know that?”

When you ask children meaningful questions they see themselves as valuable contributors to a literate classroom community. They know that they are trusted and expected to have good ideas and think for themselves.

Guidelines for open-ended questions

Keep a list of helpful question stems for your own planning purposes and continue to add to it as you think of more.

Invite children to respond to open-ended questions in partnerships or small groups to increase individual talk time.

Ask children to support their responses to open-ended questions using their prior knowledge and evidence from the text.

Model your own responses to open-ended questions during a read aloud and ask children to react or respond.

If you are having a book discussion at the end of a read aloud, re-position the children so they are facing each other in a circle to encourage conversation.

Teach children to look at the person responding to a question during a read aloud to show respect.

Encourage conversation by teaching children sentence stems for sharing their ideas such as “I think…,” “I would like to add…,” and “I also noticed…” Create and post a chart with sentence stems for sharing ideas during a read aloud for children to reference.

Allow for “wait time” after asking an open-ended question during a read aloud so your children have time to think and respond.

Accept and even encourage divergent thinking, show openness to children’s ideas, and explore different perspectives. For example:

- “You know, I hadn’t thought of it that way. Could you explain more about…”

- “What are other possible reasons?”

- “Is there another way to look at it?”

- Encourage elaboration by asking follow-up questions such as:

- “Can you tell me more about…?”

- “Can you elaborate on that idea?”

- “I’m thinking about what you said, I wonder if you can say more about that.”

- “Keep talking…”

Show genuine interest and curiosity. Ask questions such as, “I’m curious about…” “Who can tell us something about…”

Reflect on whether you are calling on children equally so that everyone has a chance to respond to open-ended questions with their thinking.

Text-Dependent Questions

Text-dependent questions help children comprehend and engage with complex texts. Text-dependent questions are questions that must be answered by going back to the text. They don’t rely on the reader’s background knowledge or experiences. These questions can be a simple recall of facts, but they can also allow you to go deeper. They can be open-ended and require critical thinking skills to answer. When you ask more text-dependent questions, children learn to look more closely at what they are reading.

Model and ask questions that specifically focus on the text during and after your read aloud. Model for children how to consider evidence from the text. You can use text-based questions to add depth to the discussion by asking children to support their thinking. Follow up on a child’s answer to an open-ended question by asking, “What in the story made you think that?” or “Tell me where in the book you saw that?”

Type of Questions

Here are examples of questions that lead children to use thoughtful examples from the text:

General Understanding

- Can you retell the story using first, next, then, and finally?

- What seems important in this book? What in the book makes you think that?

- What is the main idea? What in the book tells you that?

Key Details

- What did the characters do to try and solve the problem?

- What does the author tell us that lets us know how _________ feels?

Vocabulary & Language

- What does the word _________ mean in this sentence?

- How does the author play with words to add meaning to this paragraph?

- Why did the author choose the word _________ to describe _________?

Text Structure

- How did the author organize the text? How did this help us understand this book?

Author’s Purpose

- Why did the author write this? How do you know?

- What does the author want us to know about _________?

- Who would be interested in this? Why?

- Is the author trying to convince me of something? What? How do I know?

- Is there a message? What in the book makes you think that?

Inferences

- How do you think _________ feels? Show me what in the book made you think that.

- Do you think _________’s actions caused _________? Why?

- What do you think will happen next? What did you hear or see to make you think that?

Opinions & Arguments

- Can you tell me what the author’s opinion of the _________ is? How do you know?

- In your opinion is the character a good friend to _________?

- Do you think this is a happy book or a sad book? What in the book made you say that?

- Is there anything that could have been explained more in the book?

Problem & Solution

- What is the big problem presented in this book?

- How do you know this is a problem?

- What happens in the story and how is the problem solved?

References

Boyles, N. (2013) Closing in on close reading. Educational Leadership. 70.4.

Fisher, D. & Frey, N. (2012) Close reading in elementary schools. The Reading Teacher. 66.3., 179.188.

Comments

No comments have been posted yet.

Log in to post a comment.