Planning Instruction

A successful Writing Workshop requires careful and thoughtful planning.

To make the most of the workshop time, outline your plans for all three components: mini-lesson, work time, and share time. Think carefully about the needs of the children in your class, your curriculum’s scope and sequence, and the process that all writers use, to plan whole group and small group lessons and individual conferences. Plan for how you will assess children’s growth and needs, and how you will use that information to revise and create future plans.

The Writing Process

All writers go through the same process when developing a piece. The steps in the process usually include some amount of:

- Pre-writing - Choosing a topic, organizing ideas, outlining, or sketching

- Drafting – Composing and writing ideas down

- Revising – Adding to and changing the writing to improve organization, word choice, style, voice, and tone

- Editing – Checking the piece for mechanics and conventions, including punctuation and spelling

- Publishing – Preparing to share the piece with others

This process is essentially the same whether you are a professional author writing your fifth book, a concerned citizen writing a letter to the editor, or a child writing a retelling of last week’s birthday party. The Writing Workshop structure allows children to develop their pieces at their own pace. Some children may still be drafting, while others have moved on to revising, editing, or getting ready to publish. The process looks different depending on a child’s age and developmental stage. Children don’t usually begin revising until they have enough skills to write a narrative with a beginning, middle, and end.

Explicitly teaching the writing process promotes independence during work time. Consider creating an anchor chart with children and using a pocket chart or work board for children to post where they are in the process for that day. This will give you additional insight around your children’s identity as writers and help inform your conferring. Remember to teach and celebrate the writing process and recognize the gains they are making as young writers.

Types of Mini-Lessons

One of the most important things that writers need, of course, is explicit and direct instruction on writing habits, craft, strategies, forms, and genres. If we know what capable writers do, we need to offer a balance of mini-lessons that support our goals. We need to instruct children on all of the qualities, habits, and strategies of effective writing.

Let’s take a look at the types of lessons young writers need.

Writing Habits & Identity

These lessons help develop children’s sense of themselves as writers. They encourage children to explore their own writing and working styles. Some examples include:

- Writers keep a list of ideas that they can write about in their writing folder.

- People write books and we can too.

- Writers ask questions when they listen to a friend’s writing.

- Writers can aim to write an entry that fills up at least one entire page.

- Writers know what to do when they’ve finished a piece.

- Writers take care of the room by using materials wisely.

The Writing Process

Children benefit from understanding the process that writers go through to develop a piece. Teach lessons that explicitly help children in each phase of the writing process: pre-writing, drafting, revising, editing, and publishing. Some examples of mini-lessons to teach include:

- Writers keep a notebook of topic ideas.

- Writers think across pages to plan how their story will go.

- Writers stretch their ideas over multiple pages in their books.

- Writers get all their great ideas down and then go back and revise.

- Writers use an editing checklist to help their audience read their piece.

- Writers celebrate each other’s work.

Genres & Forms

These mini-lessons help children explore and practice different types of writing. It’s important to teach different forms of narrative, informational, and opinion writing. Some examples may include:

- Writers write for different audiences and purposes.

- Writers back up their opinions with examples.

- Writers focus on small moments to tell a story.

- Writers add labels, captions, and pictures to information books.

Writing Craft & Technique

Lessons on word choice, organization, and style help children develop their own voice and craft. Some lessons to teach may include:

- Writers learn to stay on topic in a piece of writing.

- Writers can replace general words (dog) with specific words (Dalmatian).

- Writers can vary sentence openers instead of relying on the same sentence stem.

- Writers write a few endings and choose the best one.

- Writers can add dialogue to their pieces.

- Writers create mental images for their readers with figurative language.

Editing & Mechanics

Teach children to check and correct their work to make it more readable for their audience. Examples of these types of mini-lessons include:

- Writers use a capital letter for “I”.

- Writers use resources in the room to spell an unknown word.

- Writers use spaces between words.

- Writers read their writing out loud to catch mistakes.

- Writers punctuate dialogue correctly.

- Partners can help each other edit.

- Writers use editing checklists to check their work.

Choosing Objectives

Carefully select the primary literacy objective to ensure your lessons are meaningful and provide practical outcomes. Consider what children need to know in order to write. Make sure the objective meets the needs of your children and are connected to the craft of the genre or form you are teaching.

Here are some considerations for choosing objectives:

- Choose objectives for your mini-lesson based on your curriculum’s scope and sequence, mandated learning and language standards, and the needs of your children.

- Make sure the objective is appropriate for the majority of the children in the class (not just a few children).

- Ask yourself, “What can I suggest or demonstrate to best enhance my children’s writing?” Consider the specific genre you are teaching.

- Keep a list of mini-lesson writing objectives as you teach them. This will help you keep track of the skills, strategies, and behaviors you have taught and help with future planning. Consider listing them on an anchor chart entitled “Things good writers do.”

- When appropriate, select objectives that connect to other areas of literacy instruction such as Reading Workshop, read alouds, etc. If the children are reading non-fiction texts in Reading Workshop and learning about text features, you could teach a lesson on creating a Table of Contents page for an “All About Book” in Writing Workshop.

- Choose objectives that cover all areas of writing instruction including, for example, writing habits and identities, the writing process, and editing.

- Connect your objectives to one another in longer units that allow you to explore skills and strategies in depth.

After your lesson ends, reflect on the evidence of children’s learning and whether or not the objective needs revisiting. If it does need revisiting, ask yourself if the whole group needs it or just a small group.

Planning Template

The lesson planning template can guide your planning of a successful Writing Workshop lesson. The template is sequential and is equipped with helpful prompts that focus your attention and support your thinking through the planning of each lesson component. If you would like additional support, take a look at our “notes” version of the template. Use the sample lesson plans for ideas and feel free to adapt them to use in your own classroom.

Writing Workshop Lesson Plan Template

Use this lesson plan template to guide your own planning.

Writing Workshop Lesson Plan Template in Spanish

Use this lesson plan template to guide your own planning.

Writing Workshop Lesson Plan Template (Notes)

This version of the planning template offers more support as you plan your lessons.

Sentence Starters Writing Workshop Lesson Plan Template

This lesson plan template includes sentence starters.

K Sample WW Lesson - Point and Talk

This lesson helps children organize their writing over multiple pages of a booklet.

1st Grade Sample WW Lesson - Concept Map

This lesson teaches children to plan their writing using a concept map.

2nd Grade Sample WW Lesson - Speech Bubbles

This lesson shows children how to use speech bubbles to make their writing come alive.

3rd Grade Sample WW Lesson - Write Off an Object

This lesson gives children one idea for overcoming writer’s block.

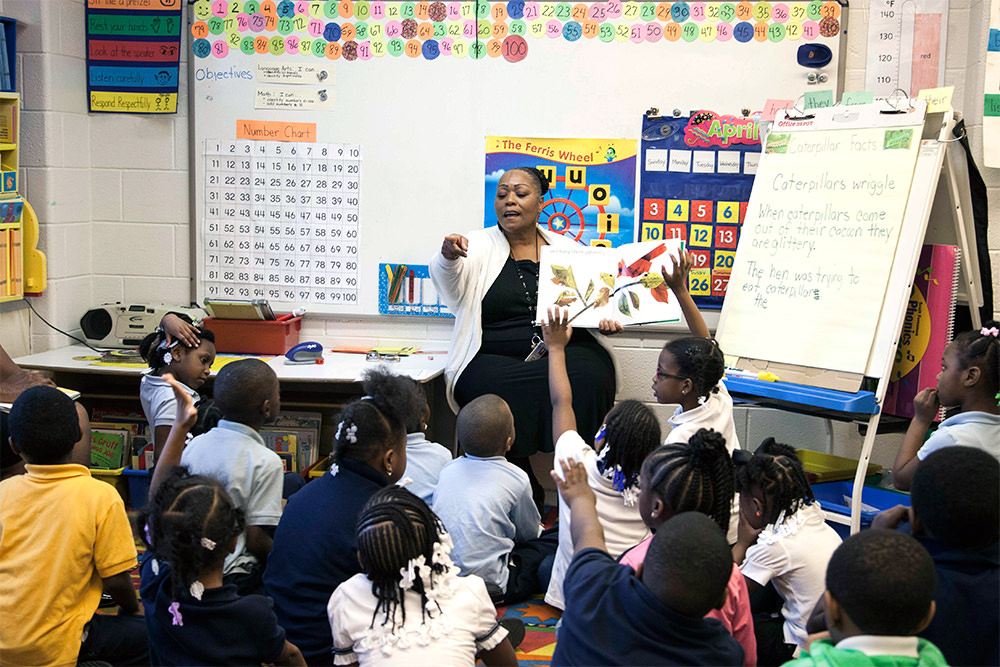

Mentor Texts

Mentor texts provide an opportunity for you to use children’s literature to provide a model for good writing and genre studies. Mentor texts are pieces of literature that can be examined and used for explicit teaching to show young writers how to shape meaning in the writing process. Through mentor texts, you have the opportunity to “show” not just “tell” children what quality writing looks and sounds like by reading authentic literature. When writers learn to listen to a story, they approach writing with a different lens that elevates expectations.

Because the children are familiar with the story line of a mentor text, each time you revisit the text you can focus on one aspect or one linguistic component of the text, instead of rereading the entire book. This is particularly helpful for Writing Workshop; one of the goals of the Writing Workshop is to ensure that the majority of time is devoted to children’s independent writing. Therefore, any reading aloud that you do for demonstration purposes in your mini-lesson, by definition, needs to be brief.

When choosing mentor texts, consider books that:

- Provide outstanding models that will help children grow as writers.

- Demonstrate the importance of choosing words wisely.

- Exemplify your teaching point.

- Stimulate creativity and create interest.

- Highlight author’s craft.

- Are rich in beautiful illustrations that add another layer to the text.

- Contain multiple life lessons.

- Are culturally diverse.

- Provide opportunities for children to explore language.

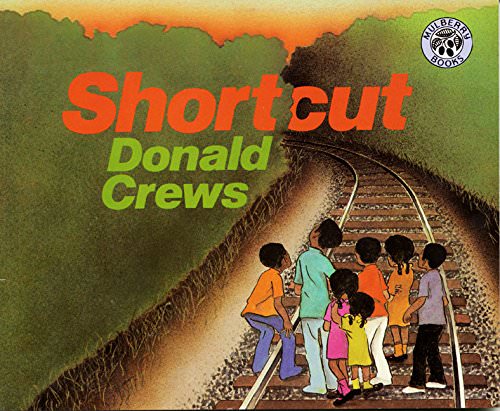

Create a list of mentor texts based on the criteria for selection above. Consider which books you love and are your children’s favorites. Get started by identifying books and keeping ongoing lists of reading topics that you can use the book to teach. For example, Short Cut by Donald Crews could be identified as a mentor text because of its focus on a small moment. Several writing lessons around small moments could come from this one book such as: zoom and focus on one part of the story, craft a strong beginning to hook readers, use onomatopoeias to build suspense, etc.

When sharing a mentor text with your children, first and foremost read it for enjoyment. Have discussions around your connections and what you liked about the story. Provide opportunities for children to share their own responses to the text. Use it in your Intentional Read Alouds, of course, and use the book to meet your objectives.

After your children are very familiar with the story line/content of the text, continue to use and refer to the book in Writing Workshop mini-lessons. During these lessons, you may only be referring to a portion of the book that matches your objective. But the children will be comfortable with this excerpt since they are so attuned to the text.

Also consider using children’s own writing as mentor texts. When you use peer’s writing as a mentor text, children see what a concept looks like in writing that matches their level of development. Featuring children’s work also increases engagement and highlights that you value their work.

Writing Assessment

In order to teach writing, you need to know what your children know. Assessment is a helpful tool to gauge children’s strengths and areas for growth, and is ongoing in Writing Workshop. Formal and informal assessments will allow you to target your instruction during large and small group instruction, and during conferences. When you assess, you are seeking to learn about your children’s writing opposed to correcting children’s work. Ask yourself, what kind of records are you keeping of your children’s growth? How are you saving their work? Below are several examples of assessment tools that can support your work in Writing Workshop.

Surveys or Interest Inventories

Inventories are simple surveys that help you get acquainted with your children. They allow you to gain insight into their attitudes about writing, their writing interests and their interests in general. These “interviews” can be conducted orally with younger children or via paper and pencil with older readers. If your child is a pre-emergent speaker of English, you can use visual cues to gather information about their interests.

Conference Notes

During work time, you will be having one-on-one time with a child conferring about his or her writing. In a conference, you have a conversation with a child about the skills and strategies that writer is using, provide direct assistance, and offer suggestions for helping the writer grow. Take notes during your conversation – for record keeping and informal assessment. A checklist is also a helpful tool to guide conversation and set goals during this time. While the tone of the conference is not about grading or correcting children’s writing, it’s an important time to gather plenty of information to help plan future instruction.

Portfolios of Writing Samples

A portfolio is a record of the writer’s journey. It should include writing and other notes children keep such as their writing plan, checklist of strategies they have used, or what they have learned in peer conferences. Use the portfolio as a tool for children to reflect on genres they have or have not used, notice patterns in their writing, identify and learn their turning points, and rank pieces from best to worst (Calkins, 1994). Allow children the opportunity to reread their portfolios and reflect on how their writing has changed or what surprises them about their writing.

Performance Assessment

Performance assessments allow you to track writers’ progress. At the end of each unit, set aside approximately forty-five minutes for children to build the best piece of writing they can based on the genre you just studied together. Use a rubric or checklist to note where children fall in the learning progression to inform future mini-lessons.

Rubrics

You can use a rubric to assess writing behaviors, writing samples, and/or writing development. You just need to be sure that the criteria on the rubric matches the instruction you are giving. In other words, you must have taught what you assess, so use the rubrics to plan your instruction. Make children aware of the expectations and goals so they know the criteria with which they are being evaluated, and explicitly teach the skills so children can be successful. Finally, you’ll need to spend some time, by yourself or in collaboration with your team members, deciding on a consistent method for turning rubrics into grades.

Rubrics allow children to know what is expected of them. The language and grading criteria (numbers, words) should be clear, consistent, and user-friendly, leaving as little room as possible for interpretation. Rubrics can be used to assess writing behaviors or children can reflect on their management of Writing Workshop time.

Checklists

Checklists can make recording observations simpler. They are designed to help remind you of the types of behaviors, processes, and understandings you are looking for during work time. Creating a checklist of observable behaviors in the workshop, particularly in writing conferences, is a valuable activity and will inherently change your instruction.

Also consider using checklists as a tool for children to self-assess. A checklist serves as a reminder for children to continue to do the kind of work they already have learned to do. With a checklist, children can assess a piece of writing and refer to the checklist to notice if they have “not met” the standard, are “starting to,” or have met standards. Children’s effort at self-improvement becomes more concrete with this scale for measuring progress.

Self-Evaluation

Writers need to be given time to self-reflect, evaluate, and assess the qualities of their own writing; this keeps them growing. If you are planning to have children self-evaluate, introduce rubrics at the beginning of a writing unit. Teach children how to use them, and encourage them to refer to the rubric throughout the writing process. At the end of the unit, allow children to self-evaluate their published piece using the rubric.

Another technique to encourage self-reflection is asking open-ended questions. Ask these questions to help your children to self-evaluate:

- Tell me something you did well in this piece of writing.

- How does this compare to other pieces you have written recently?

- Is there something you are proud of?

- Is there any place you are not fully pleased with?

After children self-assess, have them to set personal goals based on their reflection. Collaborate on a plan to reach their goal and celebrate successes along the way.

Planning Units of Study

Just like you teach units in mathematics (e.g. a few weeks on addition or fractions), writing is best taught in units too. Units of study are long term plans for focusing on one area of writing instruction that allows for depth and cohesion. Typically writing units of study focus on one particular genre of writing such as narrative, opinion, or information.

Follow these steps as you plan a unit of study:

Define your goals for the unit. Begin by identifying what you want your children to be able to learn and do based on your standards.

Brainstorm teaching ideas. What do you need to teach your children so they can advance toward these targeted outcomes? Make a list of everything you can think of and then sort, prioritize, and/or discard items that don’t contribute to the overarching outcomes.

Draft a teaching plan. Once your goals and ideas are established, create a road map of what needs to be taught daily. Your road map may be slightly different from the one for the class next door because it is based on your children’s areas of strength and needs.

Revise when necessary. Of course, your plans may need to be tweaked throughout the unit or from year to year. Be alert and responsive to what you see your writers need. Some skills and strategies may need more time, while others may be better taught in a small group.

Comments (30)

Log in to post a comment.