Instruction: Mini-Lesson

The mini-lesson will give your children the direction and support they need in order to grow as readers and work independently and successfully during work time.

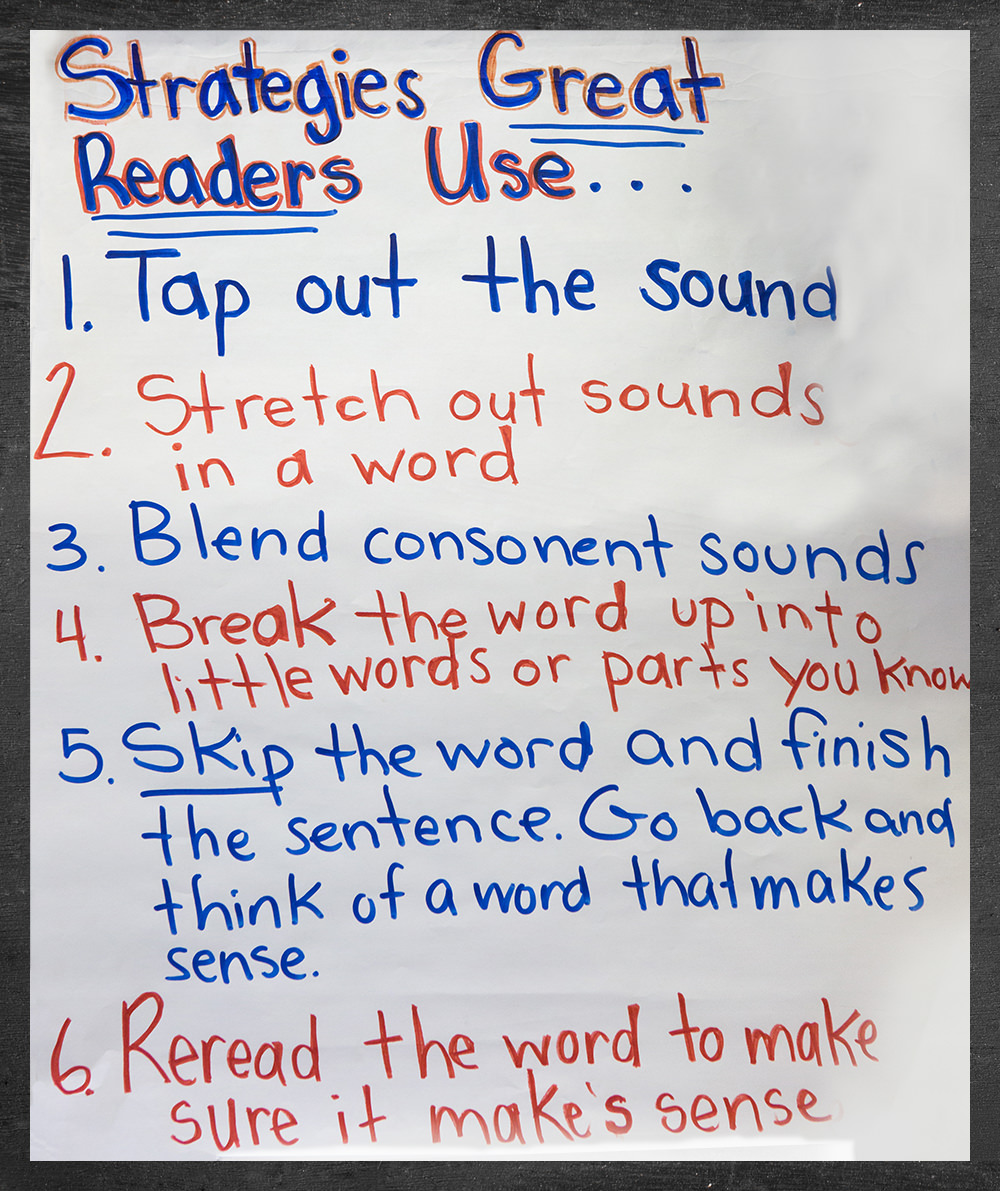

Reading Workshop In A Second Grade Classroom - Mini Lesson and Share - Strategy For Determining The Meaning Of Words

Reading Workshop In A Third Grade Classroom - Mini Lesson and Share - Asking Questions To Engage With The Text

The mini-lesson is a period of direct and explicit instruction. Teach only one literacy objective and be explicit in explaining how learning this teaching point will help your children as readers. Use a gradual release model, in which you first demonstrate the teaching point and then give the children guided practice. The mini-lesson supports children in seeing the teaching point in action and practicing it under your guidance. Linking the work they just did with you to the work they will do on their own helps prepare them for independent reading during work time.

The mini-lesson is a period of direct and explicit instruction. Teach only one literacy objective and be explicit in explaining how learning this teaching point will help your children as readers. Use a gradual release model, in which you first demonstrate the teaching point and then give the children guided practice. The mini-lesson supports children in seeing the teaching point in action and practicing it under your guidance. Linking the work they just did with you to the work they will do on their own helps prepare them for independent reading during work time.

Gather the children together in the whole group meeting area for your lessons and their sense of themselves as a community of readers will develop as well.

The Architecture of a Mini-Lesson

Reading Workshop begins with a mini-lesson which allows you to offer your children direct instruction on a reading skill, strategy, or behavior that the majority of them need. There are four distinct parts to a mini-lesson. This formal architecture makes it easier for you to plan and easier for the children to know what is expected of them and what will take place. The four parts are:

Connect - Set the context by describing the learning that has been taking place. Explain what you’ll be teaching them (that is, what the literacy objective is) and why it will help them as readers.

Teach – In this part, blend together explanation and demonstration. Explain what your demonstration will be then model the behavior, skill, or strategy. Additionally, in order to help children “see” what is happening as you process a piece of text, for example, think aloud about your process.

Have-a-Go – Give the children hands-on practice with the teaching point and assess their understanding. This takes place while the children are still in front of you in the large group meeting area.

Link – Restate the teaching point one more time. Encourage the children to plan and commit to applying it in their independent work.

Remember, the mini-lesson is designed to be brief in order to make sure that the majority of time during Reading Workshop is devoted to children reading. By sticking to this architecture and keeping questions and discussion to a minimum, you’ll be able to do just that. Offering consistent language scaffolds throughout will ensure that your language learners are included and supported as well.

The Connect

The connect is the first part of the mini-lesson and important because it sets the stage for children’s learning. Consider the language your children will need to know or be familiar with in order for the lesson to be successful and the scaffolds you can use to support them.

Start by contextualizing the lesson.

Are you sharing a new skill or strategy that is part of a larger unit? If so, let your children know. For example,

- “We have been working on many different ways to figure out unfamiliar or new words. Today I want to share a new strategy with you that you might find helpful.”

Have you noticed many children exhibiting the same need and you want to address that need in your mini-lesson? If so, state it here. For example,

- “I noticed many of you are having difficulty choosing just right books, so let me share with you one strategy I use when I want to choose a just right book.

Did you see one child doing something new or extraordinary during work time and you want to share it with the rest of the class? If so, tell the children about it here. For example,

- “I noticed Janey rereading the part of her book where she got confused. Let me show you all how to do that.”

You can tie this lesson to the learning that has been taking place in other areas of reading or content area instruction. For example,

- “Readers, today I just read The School is Not White! [show the book] to you and while I was reading it, I was asking many questions and you were too. We realized that while we read, questions naturally pop into our minds and we felt as if we dug deeper into our book and got more involved in it when we stopped to ask questions and to think about their answers. Questions matter!”

Then name your teaching point simply and explicitly. Explain why you are going to teach this idea. This allows the children to understand the importance of the skill or strategy. Cue your children so they get ready for the teaching point. Use familiar language such as, “Today, I am going to teach you” or “Today you will learn…” Also, address language supports that will be needed to implement the teaching point for your language learners. For example,

- “Today I am going to teach you how thoughtful readers ask questions not only when they listen to a story but also when they read independently. Questions matter because they allow us to linger with our texts, to get more involved, to make sure we understand the book better. We are also going to chart question words that you know, such as the WH-words like “what,” “who,” “when,” and “why.” These will help us get ready to ask questions when we read.”

Mini-Lesson: The Teach

During the mini-lesson you have the opportunity to let children “see” what your teaching point looks like in the hands of the most experienced reader in the room – YOU! Through a combination of explaining, demonstrating, and thinking aloud, you can help make the implicit (the active reading in your mind) explicit.

| Strategy | What this means | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Explain |

|

“One thing readers do when they come across a word that they do not know the meaning of is substitute a word that makes sense. Substitute means to replace one thing for another. If you are drawing a picture of a flower, and your green marker runs out, you might need to substitute your green marker for a yellow or red marker that works.” |

| Demonstrate |

|

“Let me show you what I mean. We are all familiar with the book Wolf! by Becky Bloom. I have read this book to you many times. But there are some words in this book that may be new or unfamiliar to you. Let’s look at this part:” [teacher has prewritten this section on chart paper or on an overhead and reads aloud the excerpt] “What’s wrong with you?” growled the wolf. “Can’t you see I’m a big and dangerous wolf?” “I’m sure you are,” replied the pig. “But couldn’t you be big and dangerous somewhere else? We’re trying to read. This is a farm for educated animals. Now be a good wolf and go away,” said the pig, giving him a push. “Now this word ‘educated’ is not a word I see often when I read so I’m not really sure what it means. But let me think about what is going on in the story. The pig, the duck, and the cow are all trying to read and they don’t want to be bothered by the wolf. I do think that people who like to read and don’t want to be distracted when they are read are smart. So, let me substitute the word ‘smart’ for ‘educated’ and reread that part again to see if ‘smart’ makes sense in the context of the story.” [teacher rereads, substituting the word ‘smart’ for ‘educated.’] “Yes, that does seem to make sense. So, I am thinking that educated must mean smart.” |

| Think Aloud | When you think aloud, you are describing the thinking that is going on inside your head as you do the reading work. Simplifying and being explicit about your thinking process can be especially important for language learners or struggling readers in your class. | “Did you see how I used what was happening in the story to help me find a word to replace the word I was having trouble with? Substituting a known word for an unknown word can really help you figure out the meaning of new words. And asking yourself, ‘Does that make sense?’ is essential to truly understanding the new word and the story itself.” |

Mini-Lesson: The Have-a-Go

In every mini-lesson, you will want to give children guided practice with the teaching point. This active engagement portion of the mini-lesson, also called have-a-go, occurs when the children are still gathered together in close proximity on the rug and should only take a few minutes. Remember to match the have-a-go to your teaching point so the children have some hands-on practice in preparation for their independent application of the skills or strategy later on. For example, if you demonstrated for the children how to use a glossary when reading non-fiction, then the have-a-go would allow them the chance to use a glossary right then and there. This important component of the lesson ensures that children have an opportunity to apply the new strategy with guided support. Trying it out helps them remember what you taught so they can use this strategy or technique during that work time or at some later point when they need it.

There are several ways to hold a have-a-go:

| What the children do | Why | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Try it out! | Give the children a brief experience trying out a new skill or strategy, separate from what they might go off and do in their independent work. | “Now that we know authors use different words for the word ‘said’ when they write, open up one of your books from your book baggy. Scan, or look over, one page and see if you can find a word other than ‘said’ after a set of quotation marks.” |

| Think, turn and talk | Give them time to process their learning | “Now that we have learned that readers ask questions about a book before they even begin reading it, think about why doing this can help prepare you for your reading. Now turn and talk with your neighbor about it. You can start by saying, ‘Readers ask questions before they read because…’” |

| Make a plan | Give children time to plan for their independent application of the skill, strategy, or behavior. | ““Look through the book you are planning to read today and imagine where you might be able to use the strategy we just talked about. Use one post-it note to mark the spot where you will stop to retell what has happened in your book so far.” |

Be sure to circulate among the children during the have-a-go. This guided practice time also offers you a quick assessment of how they are managing this new skill, strategy, or behavior and you can identify individuals (or groups of children) who may need extra practice.

As you consider the diverse needs of your children, remember child pairing as a possible support structure for children to begin to master the new strategy or technique.

Mini-Lesson: The Link

Before you send your children off to work independently, offer them some guidelines so they feel prepared to begin the thoughtful work of active reading. Make sure to reiterate your teaching point and direct the children to think about how they can use the teaching point that was made.

Restate the teaching point.

Use the same language in the link as you have in your connection and teach. Consistent language with identified scaffolds (for example, key vocabulary with visual cues, sentence frames, etc.) will assist children in understanding what is asked of them. For example, if you called your teaching “making mental images” in your connection, then restate it the same way in your link. Consistency in your scaffolds will also ensure all children know exactly what supports they can access when working independently.

Direct children’s independent work.

It’s important to remember that not every child in your class has to commit to working on that specific skill or strategy. For example, if you taught your first graders to use repeated patterns in books to help them with their reading, not every child may be reading a repeating book that day so they won’t all need to apply it. However, this is a tool that they now have exposure to and they can add to their reader’s toolbox to pull out when necessary. We can convey the expectation that children should try this at some point – in the next workshop or during the following week. Oftentimes, children are motivated to try what we taught when we end the mini-lesson by saying, “If you try this strategy today, please let me know.” When you are NOT asking all children to try out what you’ve taught them, be sure you have provided an alternative for what they can do during their independent work.

You can ask the children, for example, to give you a “thumbs up” if they feel ready to use the new skill or strategy; or a “thumbs down” if they have a few more questions and would like to talk more with you on the rug before beginning their work.

Ask for a show of hands. “Raise your hand if you think you can try this strategy in your reading today.”

Suggest that children incorporate what you’ve taught into their plans. “If you plan to try this today, write a note to yourself at the top of your page (an “assignment box”) to remind you to work on that.”

Then, dismiss them from the whole group meeting area to their reading spots. Make sure to be consistent in this transition so it occurs in a smooth and orderly fashion.

Be aware that language learners may not advocate for themselves in the ways suggested above; therefore, make sure you have embedded extra check-ins with them during work time.

Comments (26)

Log in to post a comment.