Before Reading

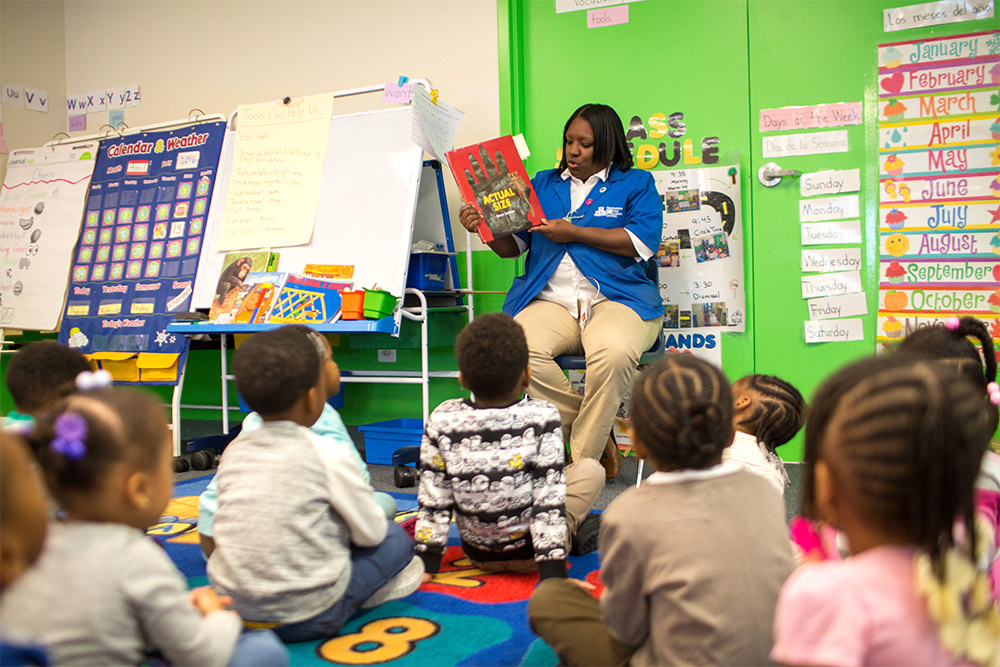

After you’ve planned your lesson and gathered the children on the carpet, take a few moments to introduce the book to the children and build anticipation for the read aloud.

As adults, we “get our minds ready to read” before we dive into a book. We do this by looking at the cover, reading the title and the author, and thinking about what we know about the topic or story. The book introduction is your time to both model this process for children and generate excitement for the story ahead. During your introduction, tell children what the learning goals are for the lesson. Set a purpose for listening and responding to the book by telling children:

During your introduction, tell children what the learning goals are for the lesson. Set a purpose for listening and responding to the book by telling children:

- what they will be learning in the lesson

- how it will help them as readers

- why you chose the book to teach the lesson

Start to build comprehension by getting children to think about the story before reading. Introduce any vocabulary that is critical to understanding the story. Connect the book to what children are learning by activating or building background knowledge, if necessary. Look at the cover or read the back of the book and have children make predictions about what might happen in the story.

Guidelines for Introducing the Book

Introduce the book to children before you begin reading to set the stage, show how books work, build comprehension, and generate interest in the text. Try to keep the introduction short and to the point, so you can spend the bulk of your read aloud time reading and talking about the book.

Essentials

- Read the title, author, and illustrator.

- Show children the illustration on the cover of the book.

- Set the purpose for listening. Explain the connection between the book and the purpose for listening.

Options

- Read the back cover, inside flaps, or dedication if the information lends insight into the book, the writing process or relates to your primary objective.

- Call attention to parts of the book. Point out and name the front and back cover, title page, and spine of the book until children can name them on their own.

- Name the genre of the book.

- Introduce vocabulary words needed to understand the book.

- Model and/or elicit predictions.

- Activate or build background knowledge needed to understand the book.

Setting the Purpose

Children will be more focused on and engaged in the lesson if they have a clear “job” to do. Before you begin reading, set the purpose of the lesson for the children. Tell them what they will be learning and how it will help them as readers in language they will understand. Explain why you chose the book you did, and how the book relates to the lesson.

Here are some ways to set the purpose for children:

| Primary Literacy Objective | Purpose | How it helps them as readers | How the purpose relates to the book |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hear and generate rhyming words | “Today we are going to listen for rhyming words in our book. Let’s see if we can figure out the rhyming pattern.” | “We might even be able to guess some words in our book based on the rhyming pattern. We can use the rhyme and think about what makes sense to guess the words.” | “I chose One Duck Stuck because it is one of our favorite books. It is silly and fun AND has a great rhyming pattern.” |

| Describe how a character changes throughout the text | “We’ve been thinking hard about the characters in our books. We’ve been trying to really get to know them by talking about what they think and how they feel. Sometimes, characters in stories change. As we read today, let’s write down how the character is feeling in the story. Let’s see how and why our character changes.” | “Good readers notice how characters in a story feel and how those feelings change throughout the story. Noticing how and why a character changes helps us get at the ‘big ideas’ or messages in the story.” | “I chose Something Beautiful because I think you’ll love the realistic illustrations and the beautiful message in the story. This is the kind of book in which the main character changes – she learns something about herself and the world.” |

| Use captions to deepen understanding of main idea in an informational text | “Today we are going to add to our anchor chart of informational text features. We’ve already talked about how diagrams, charts and illustrations can help us understand informational books. Today we are going to talk about how captions give us great information too.” | “Good readers use everything on the page to figure out the main topic and ideas in the text.” | “I have a great book to share with you today, Surprising Sharks. I’m sure you have already guessed that it is about sharks. This book has many of the text features we have learned about this year – it has diagrams, illustrations, charts, and lots and lots of facts. It also has captions that will help us get at the main ideas in the text.” |

Building and Accessing Background Knowledge

“A reader’s background knowledge affects how his attention is directed, how incoming information is interpreted, how it is stored in memory, and the ease with which it can be made available from memory. Reading is not content free; readers read about something, and the content of that something makes a big difference in how well it is understood” (Beck & McKeown, 2002.)

“A reader’s background knowledge affects how his attention is directed, how incoming information is interpreted, how it is stored in memory, and the ease with which it can be made available from memory. Reading is not content free; readers read about something, and the content of that something makes a big difference in how well it is understood” (Beck & McKeown, 2002.)

Accessing and using background knowledge is a central comprehension strategy. The intentional read aloud is the perfect place to model and teach this skill. When we read aloud to children, we show them the work we do to comprehend books by explaining our thinking and the strategies we use.

When we read books, we don’t go into them “cold.” We usually like to have some information before we dive in. We think about who wrote the book and what we know about the author. We think about the title and think about when the book was written. We might read the back of the book, or even a review. Maybe we’ve talked to a friend about the book. We use all of this information to anticipate and predict how the book will go.

It’s a good idea to do model and teach this process with children, too. Instead of simply asking children “What do you know about…?” Let’s go a little bit deeper when introducing a book.

- What information do your children already have on the topic, theme, or author?

- How will what they know help them access the book?

- What experiences have children had that will help them relate to the character or theme of a story?

- What are the potential roadblocks?

How to build background knowledge before reading

Think carefully about what children will need to understand the book.

Focus on potential stumbling blocks.

Help children connect new information to known information by activating schema before reading. Children learn when they connect new information to what they already know.

Don’t spend a lot of time building background knowledge for information that is covered in the book. For example, if you are reading Surprising Sharks, you don’t have to build background on sharks. The information they need is right in the book.

On the other hand, don’t assume children have the background knowledge they need. If you haven’t taught it, act as if they don’t know it.

Keep it brief. Building background knowledge is important, but can be quick. You’ll want plenty of time to get to the good stuff inside the book.

Consider telling children the information they need rather than ask what they know about it. Children often have misconceptions about things that can derail the conversation. Even if the information is right, it may or may not help them understand the content.

As children become skilled at accessing background knowledge, it might not be necessary for them to discuss their thinking out loud. Instead, ask children to think in their own heads about what they know about a topic, author, or text format.

Pair fiction and non-fiction books on the same topic. For example, you might pair Stella Luna, a story about a young bat, with TIME for Kids’ Bats.

Change the level of support depending on the needs of your children. Model how proficient readers build and access background knowledge, guide children to practice by asking questions, and eventually encourage them to do the work on their own.

Comments (1)

Log in to post a comment.