Instruction: Work Time

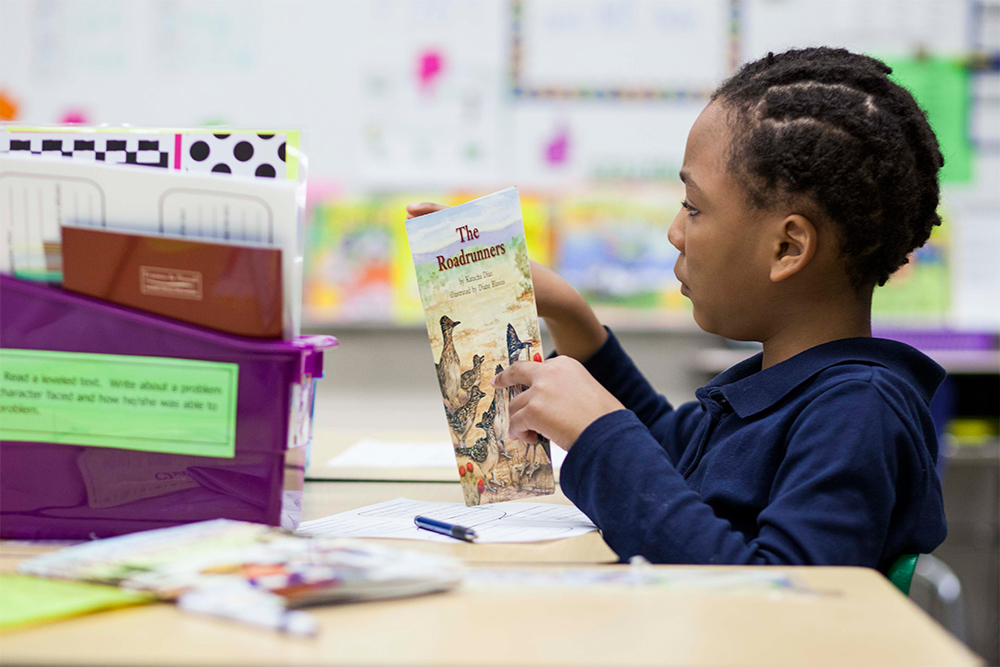

Work time is the heart of Reading Workshop. This component provides children independent time to apply the skills, strategies, and behaviors you taught them.

Reading Workshop In A Second Grade Classroom - Student Conference - Ahmed

Reading Workshop In A Third Grade Classroom - Student Conference - Jayla

Reading Workshop In A Third Grade Classroom - Student Conference - Joseph

This is when they are, in the truest sense, readers! Work time can look and sound different in each classroom depending on the children’s age, their reading levels, their language support needs, their grade level, and even time of the year. Nevertheless, there are some common threads you will see in every workshop classroom.

During work time, the children first and foremost are reading independently or with partners from books that they chose that are just right for them. Time spent on reading cannot be compromised. It is this practice that will allow children to grow as readers. While children are reading, hold conferences with a few children each day. Get to know them as readers and talk about their reading. Nurture their growth by giving them the individualized attention and instruction they need. This individualized time will allow you the opportunity to address specific literacy and language needs for each child.

During work time children may also be responding to books, working at centers, or attending small group lessons. These activities may take the form of a Guided Reading group, strategy group, or literature circle, depending again on the age of the children and their needs.

For any work time to be successful, you need to create a joyful climate in which learning to read is prioritized. Develop procedures that promote choice, independence, and active engagement. Teach explicit procedures and give children time to practice them.

Differentiation in Work Time

The purpose of work time is to have children read. The more reading they do, the stronger their reading skills will be. Practice is essential! However, Reading Workshop was designed to support all children’s literacy and language growth and therefore it’s important to consider each individual child’s academic needs. While some children will find reading time easy and natural, some of your children may be mitigating language while simultaneously mastering the process of learning to read. Other children may not have the stamina or internal motivation yet to be successful at reading the entire time you have scheduled. Therefore, you may need to differentiate work time to best meet the needs of your individual children as readers and speakers of English. Below are suggestions for how to differentiate work time with the idea that these supports will eventually allow the children who receive them to read for longer periods of time in self-selected, just right books. Consider the age, reading levels, language needs, and time of the year when incorporating these differentiation strategies.

The purpose of work time is to have children read. The more reading they do, the stronger their reading skills will be. Practice is essential! However, Reading Workshop was designed to support all children’s literacy and language growth and therefore it’s important to consider each individual child’s academic needs. While some children will find reading time easy and natural, some of your children may be mitigating language while simultaneously mastering the process of learning to read. Other children may not have the stamina or internal motivation yet to be successful at reading the entire time you have scheduled. Therefore, you may need to differentiate work time to best meet the needs of your individual children as readers and speakers of English. Below are suggestions for how to differentiate work time with the idea that these supports will eventually allow the children who receive them to read for longer periods of time in self-selected, just right books. Consider the age, reading levels, language needs, and time of the year when incorporating these differentiation strategies.

Listen to a book. Listening to audiobooks gives children experience with book language and story structure which is important as they develop as readers. Children who may not have the stamina or skills to read during the entire work time may benefit from listening to books. Audiobooks can be used in multiple ways. Children can listen to books that you have read aloud to them at other times of the day. The text is familiar and therefore will be engaging to the listener. Or you can introduce children to new books above their reading level while providing them a model of fluent, expressive reading, exposure to new vocabulary, and practice with comprehension. Conversely the children may also read aloud and create books for their classmates to listen to. This provides the opportunity for the language learner to continue building fluency and prosody with real outcomes.

Read a familiar text. Offer children the opportunity to revisit big books or other picture books you have read aloud. Their familiarity with the text will support and engage them in rereading the books.

Read a challenging text. Sometimes there are books that children really want to read but are above the children’s reading levels. Give children the opportunity to explore these books and talk to them about how they make sense of books they are unable to read conventionally. Oftentimes, books that are slightly above children’s reading levels but are of high interest to them can provide just the right motivation to work hard.

Write about their reading. As children build their stamina, built-in breaks can be rejuvenating. You can ask those children that need it to draw or write about their book in a purposeful way. For children mitigating language this provides a nice opportunity to explore new language, vocabulary, and structures. These connections should be highly individualized depending upon English language development needs.

Talk to a partner. If partnerships are not routine in your classroom, give children the opportunity to process their thinking and take a mental break from the work of reading by encouraging talk time. Adding opportunities for authentic talk during reading time is a great strategy for many children.

Building Children’s Stamina

Just as athletes train each and every day to go farther, to be stronger, and to reach their athletic goals, children need to train in their own way each and every day to reach their literacy goals. Building children’s reading stamina is one important way they can build their literacy muscles. Work time during Reading Workshop is the perfect time to help children learn how to increase their stamina and give them practice doing so.

Just as athletes train each and every day to go farther, to be stronger, and to reach their athletic goals, children need to train in their own way each and every day to reach their literacy goals. Building children’s reading stamina is one important way they can build their literacy muscles. Work time during Reading Workshop is the perfect time to help children learn how to increase their stamina and give them practice doing so.

Reading stamina is a child’s ability to focus and read independently for a period of time and is something that grows over the course of time with intentional practice. How long children will be able to read depends, of course, on a number of factors such as their age, their access to materials that interest them, and their experience with reading and language. While there are no absolutely firm numbers, researchers agree that by the middle to the end of the year, kindergartners should read up to 15 minutes, first graders 20 minutes, second graders 25 minutes and so on. Conversely, as you consider the needs of your English language learners, the stamina building may not mirror the same trajectory as your native language speakers. These children are both negotiating the skill of learning to read and learning to read in English. As teachers, you can help children build reading stamina in a number of ways.

Time Oriented vs. Task Oriented

Typically, classrooms tend to be task oriented, with children working on assignments such as a completing a page in a workbook or writing a paragraph about their favorite character. However, to build reading stamina, consider shifting the focus from reading tasks to reading time. During work time, help children realize that when it’s “reading time” in your classroom you expect children to do just that - spend time actively engaged in reading. Reading time doesn’t end when a book or a chapter is completed; rather reading ends when the time scheduled for it is over. Teach children what to do when they are done with a book. Should they write a book recommendation and post it where their friends can see it? Should they put post-it notes in the book on pages about which they want to talk to their reading partner? Should they begin a new book right away? Consider the needs and interests of the children in your class as you begin to offer your readers options for what to do when they finish a book in order to help them build their stamina.

Different Reading Spaces

To help children build stamina, consider the space in your classroom. Just as mature readers have favorite places to read, consider how you can create inviting spaces in your classroom where children will also feel inclined to “get lost” in their books. Some children prefer sitting at their desks, others prefer to recline on the floor. Allow for differentiation in order to meet the needs of your individual learners.

Just Right Books

Teaching children how to select a “just right” book is essential to helping them build reading stamina as well. After all, if they aren’t interested and able to read the books they have, they are more likely to get distracted. Help children learn how to take a “book walk” during which they learn how to select a book by looking at its front and back cover, browsing through its pages, looking at the pictures, and testing out the words. If the book looks interesting to them and they can read most of the words and understand what they are reading (enough, for example, to share with someone what is happening in the story or what they are learning), then they are more likely to stay engaged. Teach children how to keep books “on deck,” that is, how to keep running lists (on paper or by heart) of books they want to read next. Also teach them to look for other books by beloved authors or in series they enjoy. Giving children time to read books that may be challenging but of high interest can also aid in increasing the time children spend with text. Considering the needs of English language learners, children may need additional access to early decodables to continue practicing early literacy skills.

Reading Materials

Books aren’t the only supplies readers with stamina need. Give the children baggies filled with all the other reading materials they might need – for example, pencils, post-it notes, and bookmarks with reading strategies that might help them decode unknown words. The confidence that comes with having all your supplies next to you allows you to remain focused on your books. Some additional tools for English language learners may include a child-created visual dictionary with new words they learn during independent reading time.

More Talk

While reading is a solitary endeavor, learning can be a social activity. Consider incorporating time for reading partners to talk, share, and ask each other questions. These exchanges can allow children to re-focus on their independent reading when the time comes. When considering partnerships you may consider partnering language learners that share a first language so that they can discuss their reading more freely.

Active Reading

Children’s stamina will increase greatly if they are engaged while reading. Teach children how to make predictions, visualize, make connections, think about important ideas, and ask questions. Being an active reader - a reader who “talks” back to their books - will help with engagement. Of course, it’s quite natural sometimes to lose focus while reading. Help children learn to recognize when they have lost focus (Is your mind wandering? Are you looking away from your book more than you are looking at it? Do you remember what you just read?) and teach them how to get back on track (for example, by rereading the last section they remember).

Reading Partnerships

While the act of reading may be a solitary one between the book and the reader, reading time itself need not be. Time for children to read together and talk about their books together are essential elements of an engaging Reading Workshop. It is well-understood that when children are given opportunities using authentic language it ensures academic achievement. This talk allows them to process and respond to their reading; in other words to become active readers. Reading partnerships are one tool you can use to strengthen children’s engagement in reading.

Reading partnerships serve many different functions depending on children’s age, literacy experience, language proficiency, and grade level. For example, in younger grades, when building stamina is essential, reading partnerships allow you to do just that. Give children time to read (sitting back to back with their reading partner) and then give them talk time (sitting knee to knee) to talk about their books. This talk time allows them to share their thinking. When they are done talking, you can ask them to return to independent reading for a few more minutes (back to back). This structure gives the children a quick mental break, lets them share their thinking, and re-energizes them for more reading time. An additional benefit to this system is that when children know they have time to talk, it helps them manage their on-task behavior.

Reading partners may also spend time reading and talking about the same book. These partnerships (which can take place right after the second read described above), are multi-purposeful. They help children learn to talk about their books, they support cooperation and self-regulation, and they support strengthening children’s reading identities. Generally, reading partners tend to be on or around the same reading level. This facilitates the sharing of books that both partners can read with similar accuracy. However, being flexible with reading partnerships also has its benefits. Children with different reading or language levels will find partnerships mutually beneficial as well if, for instance, they share the same interests.

Below are some ideas for mini-lessons that you can teach to support reading partnerships in your classroom.

Mini-lessons around partnerships:

- Partners sit side by side and read with the book in the middle so they can both see the book

- Partners can choral read so they both get practice reading

- Partners can take turns reading so they each get time to read

- Partners take turns making decisions so they feel that everything is fair

- Partners read using quiet voices so other partnerships can work

- Partners talk about their books so they share their ideas

- Partners can solve problems so they can get good reading work done

- Partners look at each other when they talk so they know they’re listening

- Partners think about what each other are saying so they can answer

- Partners ask questions when they don’t understand what their partner said so their partner’s ideas are clear

- Partners help each other when they get stuck on a word so they become stronger readers

- Partners complement each other so they feel good about their reading

- Partners use sentences starters if they don’t know what to say so they can become better at reading conversations

As children become transitional and fluent readers, partnerships often evolve. They tend to take place at the end of work time and are generally more focused on the sharing of strategies. They may also evolve into book clubs or literature circles. Nevertheless, many if not all of the lessons described above would still be relevant.

Adapted from Growing Readers, Collins, K. (2004)

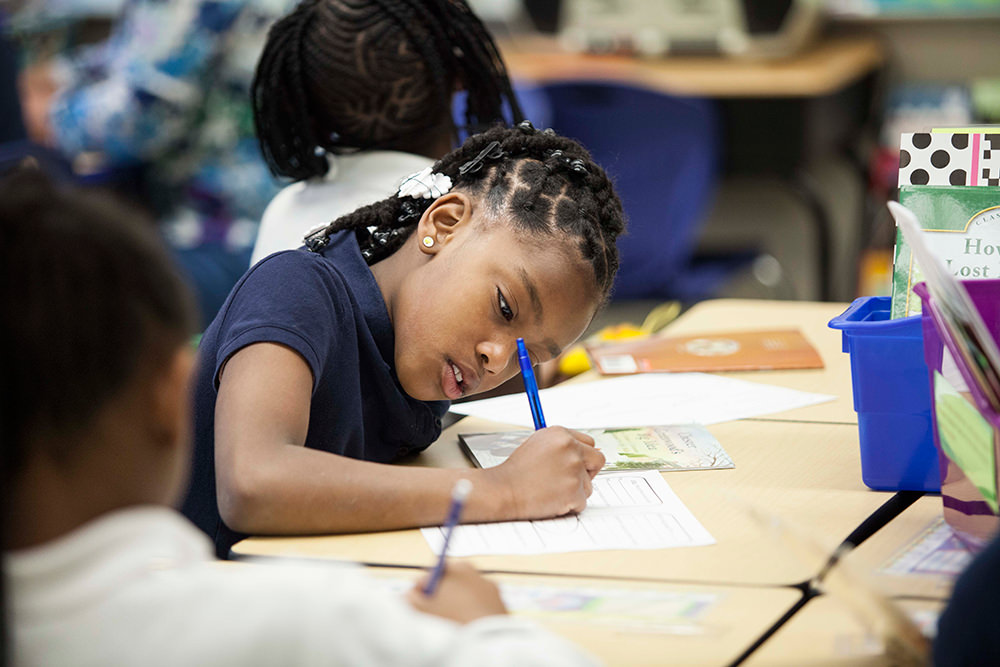

Responding to Reading

For the majority of work time, children will no doubt be reading since this will be one of the best things they can do to grow as readers. However, teaching and encouraging children how to respond to their books in writing will help them grow as readers as well. Given the time to reflect and process their information can assist them in thinking more deeply about their books. Additionally, Sharon Taberski says responding to books can actually help children build their stamina. As she states in Comprehension from the Ground Up, “to read more … provide opportunities for them to take natural breaks from their reading so they can process the new information, skills, and strategies they’re learning.” Below are a few ways children can respond to their reading in writing:

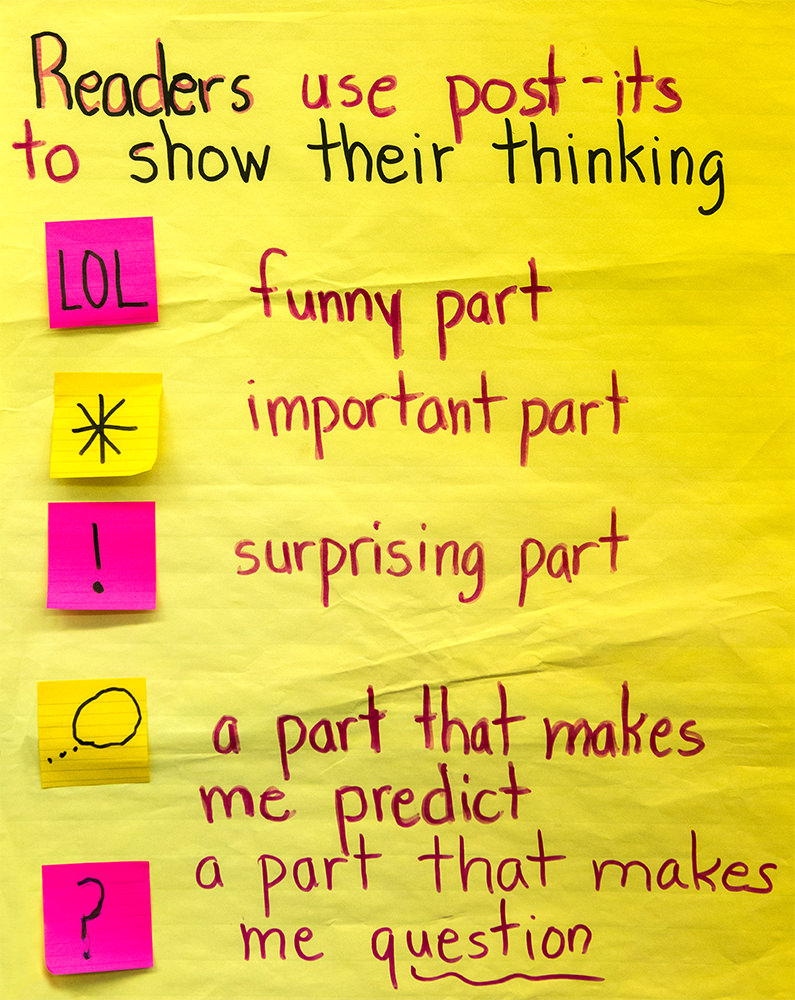

Post-it notes

These are vitally important for supporting active reading. The small size of a Post-it Note helps children learn to jot just the most important thing they are thinking. Or, they can code their thinking in a way that saves time yet allows them to process their thinking (for example, using a question mark when they are thinking of a question they would like to ask a character or the author). Additionally, when you conference with a child or when children work in partnerships, these post-its can work as springboards for conversations. The Post-it strategy is especially helpful with content specific vocabulary development. Children can mark key words that were challenging, interesting, or added to their understanding of the reading.

These are vitally important for supporting active reading. The small size of a Post-it Note helps children learn to jot just the most important thing they are thinking. Or, they can code their thinking in a way that saves time yet allows them to process their thinking (for example, using a question mark when they are thinking of a question they would like to ask a character or the author). Additionally, when you conference with a child or when children work in partnerships, these post-its can work as springboards for conversations. The Post-it strategy is especially helpful with content specific vocabulary development. Children can mark key words that were challenging, interesting, or added to their understanding of the reading.

Reading Logs

These are useful tools for having children record information about the books they have read. Depending on your grade level, the time of the year, and what you may have taught, you might also ask your children to write down the author’s name, the genre of the book, and a comment or review. More advanced readers and writers might do this for every book they read or every time they read, but early and emergent readers might only do this a few times a week.

Simply filling out a reading log may give children a sense of accomplishment (“Look how many books I read this month! I filled up my whole page!”) but it becomes incredibly powerful when linked to personal reflection. Give children time to look over their reading logs in order to learn more about themselves as readers. Give them guiding questions that lead to setting goals such as:

What types of books do I like to read? This question can help them identify the genres or authors they like and want to stick with or the types of books they are missing out on. As a goal, they might want to challenge themselves to read a book in an unfamiliar genre.

How many books do I read each week? Building stamina is very important. According to Lucy Calkins in A Guide to the Reading Workshop, giving children the opportunity to analyze, the number of minutes they read, or the number of books they read each week will assist with setting goals around stamina.

Response Sheets

These are open-ended templates that allow children to respond to how they used a particular strategy that you taught them. These are not fill-in-the blank worksheets but rather tools that help readers become more meta-cognitive about their own thinking before, during, or after they read. Providing word banks or sentence starters can support your language learners.

These are open-ended templates that allow children to respond to how they used a particular strategy that you taught them. These are not fill-in-the blank worksheets but rather tools that help readers become more meta-cognitive about their own thinking before, during, or after they read. Providing word banks or sentence starters can support your language learners.

Response Sheet - Fiction

This response sheet focuses on children's response to fiction.

Response Sheet - Informational

This response sheet focuses on children's response to informational text.

Response Sheet - Vocabulary

This response sheet focusees on children's vocabulary acquisition.

Reading Folder/Reading Notebook

This is a tool that has endless possibilities because it houses all the thinking children do about reading. It can include a section for the above-mentioned reading log and reading response sheets. Some notebooks contain vocabulary words the children are learning and some contain a section where they attach their post-it notes from their books and analyze their responses. The writing they do in this notebook can consist of jotted notes, time lines, informal records or thoughts, quick entries, and (less frequent) elaborated, developed essays. Much of the writing about reading won’t be fancy or long, but it will brim with ideas. Teach children to write fast and furiously, to “write short” often and to “write long” occasionally. Gear the work you ask them to do based on their age, the time of the year, and your curricular goals. As you create the reading folder/notebook consider what anchor charts you have co-created with your children that can be copied for this resource. This way children are more apt to use a variety of tools and strategies.

Remember, telling children to write regularly about every little bit of reading they do will definitely NOT help them become stronger readers. It is safe to say that some of us would not choose to read if every text we read needed to be accompanied by entries and essays, book reviews, and letters to an author, a classmate, or a teacher. Even after your children have increased their stamina and are actively reading, the writing you ask them to do in response to reading should not interfere with that reading but enhance it.

What is a Conference?

A conference is a purposeful conversation between you and one reader. It is designed to allow you to differentiate your instruction to meet that individual child’s needs. It’s also a wonderful time to get to know your children, their reading identities, and how reading connects to their life experiences.

Because a conference is a conversation, it can feel a little different from most teacher-child interactions. A conference is designed to draw the child out. Through the use of open-ended questions, you learn about the child’s strengths, needs, interests, and goals as a reader. Children need time and practice learning about their role in a conference so lessons that you teach that clearly explain why you want to talk with them and what you are hoping to accomplish during a conference will be helpful.

Conferences are structured conversations. There’s a general architecture to a conference in order for you to both learn what the child is doing well and how you want them to grow. This architecture helps make the children comfortable; they come to understand the patterns in the conversation, and as a result feel comfortable with the expectations. While the structure empowers children it might also seem a little unusual for you because of its open-ended nature.

Once you begin talking to children, you’ll find that you will have many ideas for how they might grow. The tricky part is selecting one of those paths. Use your knowledge of the child as they both grow as a reader and are acquiring language in Reading Workshop, the general needs of readers at that level, and the information you gather from your conversation to help guide your selection of the targeted teaching point.

Typically, conferences last between three and 10 minutes, depending on the age of the children, the topic of conversation, the children’s comfort with this kind of interaction (and yours), and the time of the year. Make sure to keep anecdotal records during your conference so you can track children’s progress and growth.

Structured Conference Recording Form

This recording sheet will help structure your conferences.

Conference Recording Form with Prompts

This recording sheet contains prompts to help guide your conferences.

The Structure of a Reading Conference

Conferences are opportunities to hold short conversations with individual readers in your room. These are conversations that help you understand your children’s interests and passions, their thought processes as both a reader and as they acquire the language of literature, their strengths, and their needs. They quickly become a favorite time for everyone involved. In order to ensure that your conversations give you the information you need to both learn more about your individual children and help guide them in their reading development, conferences typically follow the following structure:

Research → Decide → Praise → Teach

This structure also makes it easier for the children to know what is expected of them and what will take place.

| Research | Decide |

|---|---|

|

Begin your conference by asking open-ended questions in order to learn what the child is able to do as reader and what you think the next step might be for the child. For example: “Hi Rita. Tell me about the book you are reading.” |

Now that you have done your research, you need to make some decisions. What is this reader doing well that you can name? Based on what you know about reading development, what skill, strategy, or behavior might you offer this child in order to help them grow? These are decisions you will have to make in the moment, during your conversation. |

| Praise | Teach |

|---|---|

|

Name something the child is doing well. Consider how you can relate it to what the child needs to do next. “Wow, Rita. You just told me that you are reading a book that rhymes and when I listened to you read, I heard you put extra special bounce into your voice each time you found words that rhymed.” |

Offer one skill, strategy or behavior that will help this child move forward as a reader. Remember to “teach the reader, not the reading.” In other words, look for something universal that you can teach, that can be applied regardless of the book that child is reading. You might begin like this, for example: “I also noticed there was a tricky word in the book and I wanted to teach you one way that you can figure out tricky words. If you know that the last word on each page rhymes, you can use the rhyming pattern to help you figure out the tricky word. Let me show you how I would do it.” [demonstrate] |

Text Bands

Adapted from A Guide to the Reading Workshop, Calkins, L. (2015)

When you run a workshop classroom, you are probably going to find that you have a wide range of readers in your room, reading books at all different levels. Below is a guide to what children at different levels are primarily working on and the characteristics of the books they are reading. This information can help you know what skills to support and teach in conferences and other reading lessons.

| Levels | Children at these levels need to work on… | Book Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| A/B |

|

|

| C/D |

|

|

| E/F |

|

|

| G/H/I |

|

|

| J/K/L/M |

|

|

| N/O/P |

|

|

Open-Ended Questions

Conversations with readers can go in many different directions. Over time, you want to conference with your children about a full range of topics that speak to the multidimensionality of their lives as readers and their ability to employ academic language to discuss their reading. However, remember that a conference is a conversation and therefore, whatever topic arises, you want to use open-ended questions to draw out the child’s thinking. The more you know about the child and how the child thinks about reading and the child’s ability to communicate about their reading, the better informed your teaching decisions will be. Below are general open-ended questions you can ask children to learn more about them as readers. You might find these particularly helpful at the beginning of the year when you are first getting to know your children as readers.

| Types of Conference | Sample Open-Ended Questions |

|---|---|

| Enjoyment |

|

| Talk |

|

| Plans |

|

| Habits |

|

| Book Choices |

|

| Process |

|

| Thinking While Reading |

|

Supporting English Language Learners with Appropriate Open-Ended Questions

Research indicates that high levels of engagement and opportunities for authentic, productive language can correspond positively to a child’s future academic achievement. During reading conferences, use your knowledge of your language learners’ stages of development to craft questions that align with their ability to respond. Here are some suggested open-ended language and question stems that align to a child’s English language proficiency level or stage of acquiring English.

English Language Proficiency

| Stage of Language Development | Characteristics of child | Open-Ended Language Stems |

|---|---|---|

| Preproduction |

|

|

| Early Production |

|

|

| Speech Emergence |

|

|

| Intermediate Fluency |

|

|

| Advanced Fluency |

|

|

Krashen, Stephen D. &Terrell, Tracy. (1983). The Natural Approach: Language Acquisition in the Classroom. Oxford, England: Pergamon.

Who Gets To Share?

Selecting individuals to share during share time can be exciting. It’s a chance for you to shine the light on individuals who are doing well as independent readers. They get to be “famous” for a few minutes as they discuss their reading successes, growth, and identities. The seeds for share time, though, are planted during work time. During work time, keep your eye out for individuals who would benefit from the opportunity to share. Keep in mind how the share can support your mini-lesson and extend children’s understanding of what it means to be a strong reader by being strategic with your share choices.

Keep these questions in mind as you make your decisions:

- Who is using the teaching point well?

- Who is using a previously taught teaching point well?

- Who has been innovative and tried something new that the class would benefit hearing about?

- Who have you conferenced with? What elements of that conference can you promote?

- Who hasn’t had a chance to share recently?

- Who has demonstrated an individual or unique connection to the teaching point?

Also make sure you have structures in place to ensure that all children have an opportunity in the spotlight regardless of reading proficiency or speaking proficiency levels.

Comments (27)

Log in to post a comment.